As a public art gallery, one of KWAG’s core purposes is to steward our Permanent Collection, which now numbers over 4300 works of art that we retain for present and future generations. That duty of care goes largely unseen in the racks and rooms where artworks are safeguarded from the elements, but sometimes more active measures are needed to ensure a work of art will remain stable into the future.

Art conservation – the painstakingly careful processes by which damaged works of art are protected from ruin – requires a significant investment of time and labour that can challenge the limited budgets of public galleries and museums. Thankfully, KWAG found extraordinary support when it came to the conservation of an untitled Maurice Cullen drawing that entered our Collection in 1973.

The Artwork

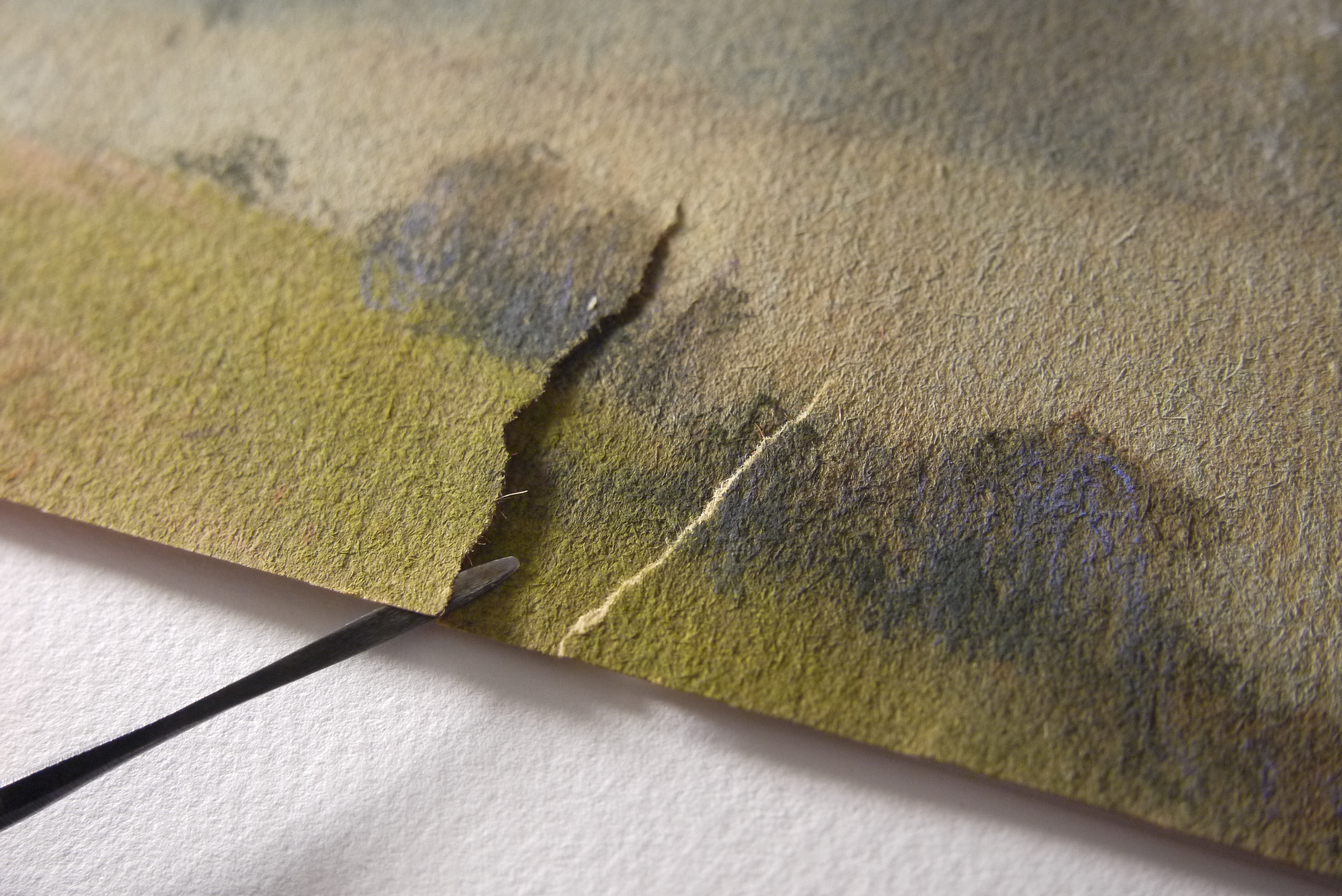

Untitled (Moonlight Over the Bay) was created by the renowned early Canadian painter Maurice Cullen around 1896, and was gifted to KWAG by the estate of Col. H.J. Heasley in 1973. Those intervening years were less than kind to this beautifully atmospheric pastel drawing – it didn’t take a magnifying glass to see the visible tears around the paper’s edges. While Cullen’s delicate use of pastels allowed much of the paper’s fawn-brown colour to remain visible through the drawing and add warmth to his landscape, a small area of the drawing had also suffered a scrape that exposed even more of the fragile, fibrous surface.

Maurice Cullen (Canadian, 1866-1934). Untitled (Moonlight Over the Bay), c. 1896. Pastel on paper, 29.8cm x 45.5cm. Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery Collection. Gift of the Estate of Col. H.J. Heasley, 1973. Photo: KWAG.

As a result, this delicate drawing was kept unframed in a flat storage drawer and seldom saw the light of day. When selected for inclusion in our 2017 exhibition Making Shade, Registrar and Assistant Curator Jennifer Bullock insisted that it be among the many works displayed flat as framing would prove too great a risk to the drawing. “I made it clear that it was super delicate and had to be moved very carefully,” she said. “The paper is so soft that it flops almost like fine fabric in your hands, if you’re not careful. I forbade in-house framing because of the condition.”

The Benefactor

Making Shade featured over a hundred drawings from our Permanent Collection when it opened in our Main Gallery in summer 2017, many of which were displayed flat in glass-topped trestle tables. Even when modestly presented among many stunning works, Maurice Cullen’s Untitled (Moonlight Over the Bay) quickly caught the attention of one of our Board directors during a pre-meeting tour of Making Shade. ‘Murray Gamble was standing next to me when I was looking at the Cullen,’ recalled Shirley Madill, our Executive Director. ‘We were both surprised to see it, realizing we had this in the Collection and it is hardly shown.’

Murray Gamble immediately offered to cover the costs of framing this drawing so that it might be shown more prominently in the future. Far from being discouraged by learning that the drawing was too fragile to withstand framing, he also agreed to fund the conservation work required to stabilize the work – ensuring it could be exhibited at any time in the future. ‘That was inspiring,’ Shirley said. ‘Rather like giving the artwork a public life.’

The Conservator

The vital work of conserving our Maurice Cullen was entrusted to Jennifer Robertson, a private practicing conservator who specializes in works on paper, including fine art, archival materials and rare books. The clients who seek out her solo conservation studio range from individuals with private collections and family treasures to university archives and art museums like KWAG.

Jennifer’s examination of our Cullen drawing under different lighting conditions revealed few surprises beyond the damage already documented by our Curatorial staff. Beyond the tears to the paper and the small scrape on the drawing’s surface, the back side of the paper showed some discolouration due to age and exposure – though no more than would be expected for a drawing well over a century old. ‘Cullen used good quality artists’ drawing paper, which tends to age well,’ Jennifer noted, pointing out that the materials artists choose can have a big impact on how the work will age over time. ‘It was in good condition for its age.’

Her primary task was to carefully repair those tears – a job best left to a professional given the many DIY adhesives Jennifer has had to remove in her line of work. Aging artifacts have come to her with homemade repairs in scotch tape, masking tape – even actual Band-Aids. “They just wanted to hold it together, so they used what they have.”

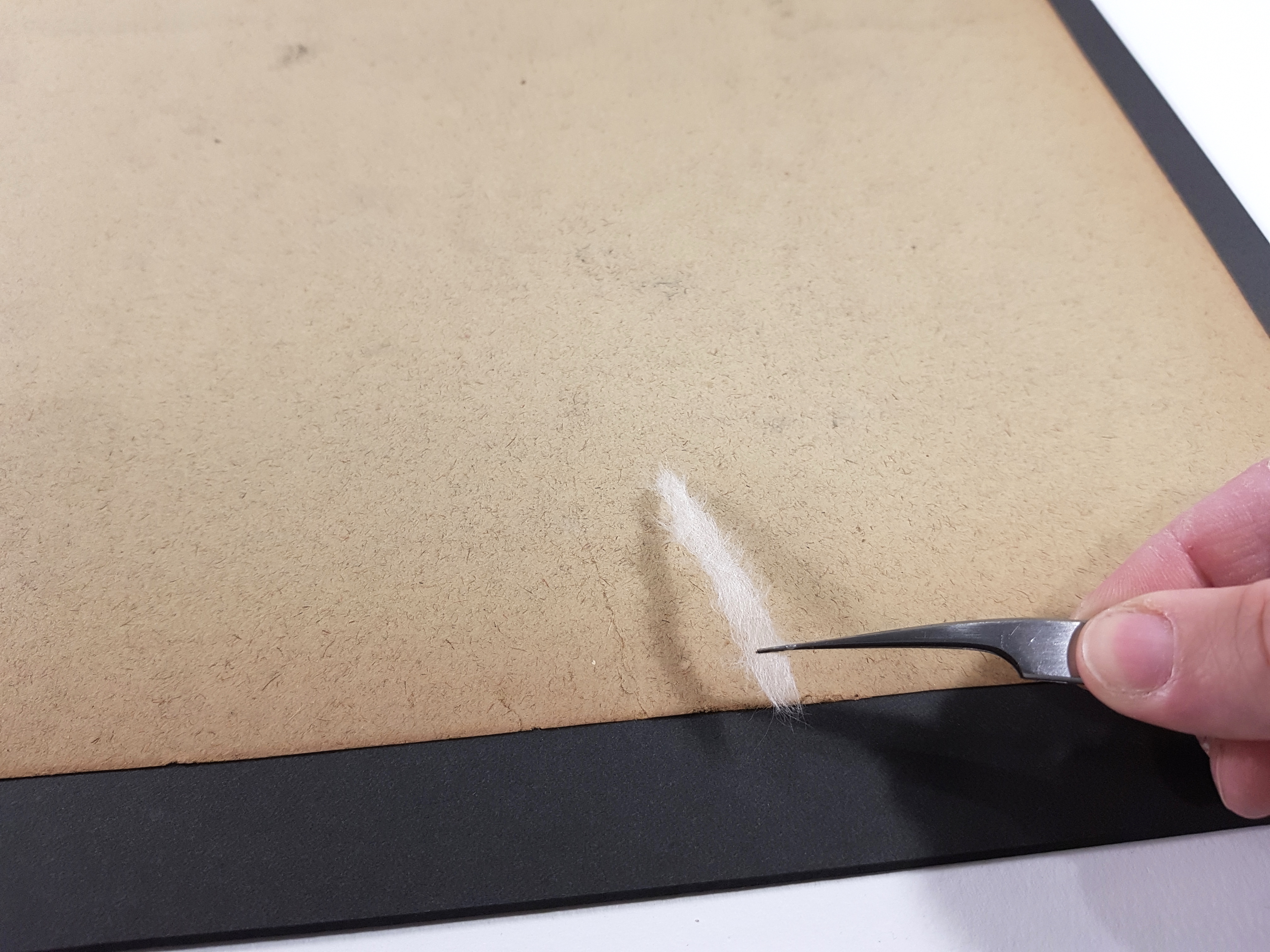

When approaching repairs such as this, conservators use stable, high-quality materials that won’t deteriorate over time, and can be easily reversed at a later date if needed. For our Cullen, this meant using conservation grade wheat starch paste to adhere the torn edges of the paper while working under magnification to ensure the weave of the paper’s fibres were aligned to their original positions. While most of the tears were clean enough to create a perfect fit, one tear in the top left did require more encouragement to nudge the paper’s weave into position.

The resulting overlap from this repair remains visible under a raking light – and that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The goal of conservation is to prevent further harm and allow a viewer to appreciate the artwork without being distracted by the damage, but hiding that damage completely would be deemed unethical. Without evidence of these repairs, a work of art could be falsified and resold as a pristine piece – and become damaged again if not handled with the exceptional care required. ‘If you can get to the point technically that you can’t see it, that’s great,” Jennifer said, ‘but it should be evident that the damage was there, at least under close examination.’

That same ethical care is even more apparent in the tricky task of inpainting damaged surfaces on the artwork itself. This is often where well-meaning restorations go horribly wrong, as it takes a strong eye for colour and an awareness of how light will change colour perception to fill in the blanks of a damaged artwork. The small scraped area on the Cullen drawing presented a relatively simple task as the area impacted did not contain any intricate details; Jennifer was able to match Cullen’s loose layers of colour with a careful combination of watercolour and pastel powder – materials that are water soluble and can be lifted from the paper by future conservators if required.

With some reinforcement on the drawing’s reverse side with Japanese paper and the application of hinges made from the same material, our Maurice Cullen was repaired, well protected and ready for framing.

Conservation is a practice that is often hidden behind the scenes of any museum collection, but the work of trained professionals like Jennifer Robertson is critical to preserving works of art for our future generations. This is also work that wouldn’t be possible without the visionary support of donors like Murray Gamble, whose personal enthusiasm for Maurice Cullen inspired him to ‘adopt’ this artwork. Together, they have ensured that Untitled (Moonlight Over the Bay) can be safely displayed for many more years to come.

You can learn more about Jennifer Robertson and her work by checking out Book & Paper Conservation and following her on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. To learn more about art conservation, be sure to check out the Canadian Association for the Conservation of Cultural Property.