One month after Erratic Behaviour opened to an absolutely packed audience (and despite mining almost too many rock related puns), KWAG Curator Darryn Doull reached out to the guest curator of the exhibition, Katie Lawson, to talk origins, memories and futures.

The following conversation was conducted by written exchange in March 2024.

DD: Early on in the process of organizing this exhibition, you told me that this is an idea that you have been developing and revisiting for some time now. Do you remember how this project first came to capture your attention? How has it evolved since?

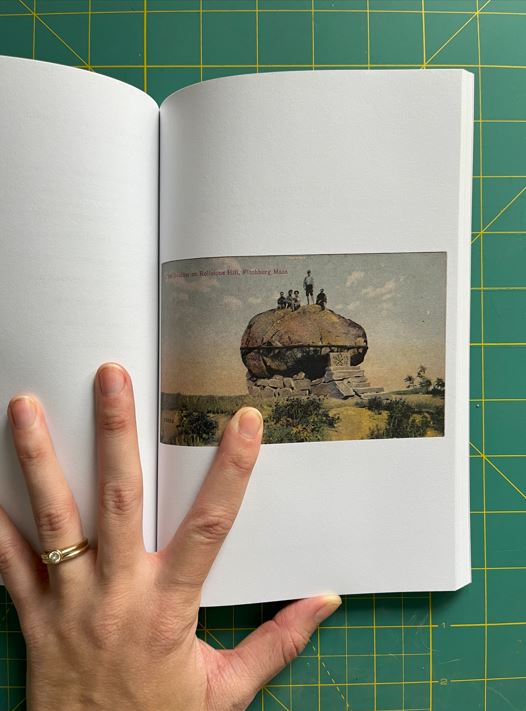

KL: As a curator I’m very drawn to working with the elements as organizing principles – a lot of my previous work has been more directly tied to water, but I knew I would eventually bring in my lifelong interest in rocks. I still remember the moment that the seed for the exhibition was planted, I describe in the curatorial essay that in 2018 during a studio visit with Meghan Price she shared her personal collection of antique postcards of erratic boulders (the very same ones right at the entrance to Erratic Behaviour). I couldn’t get some of these images out of my head and felt they embodied many of the questions I had about our relationship with the geologic. The original purpose of this visit was to develop a contribution from Meghan for the Hart House Review (I was the art editor for the literary arts publication at the time).

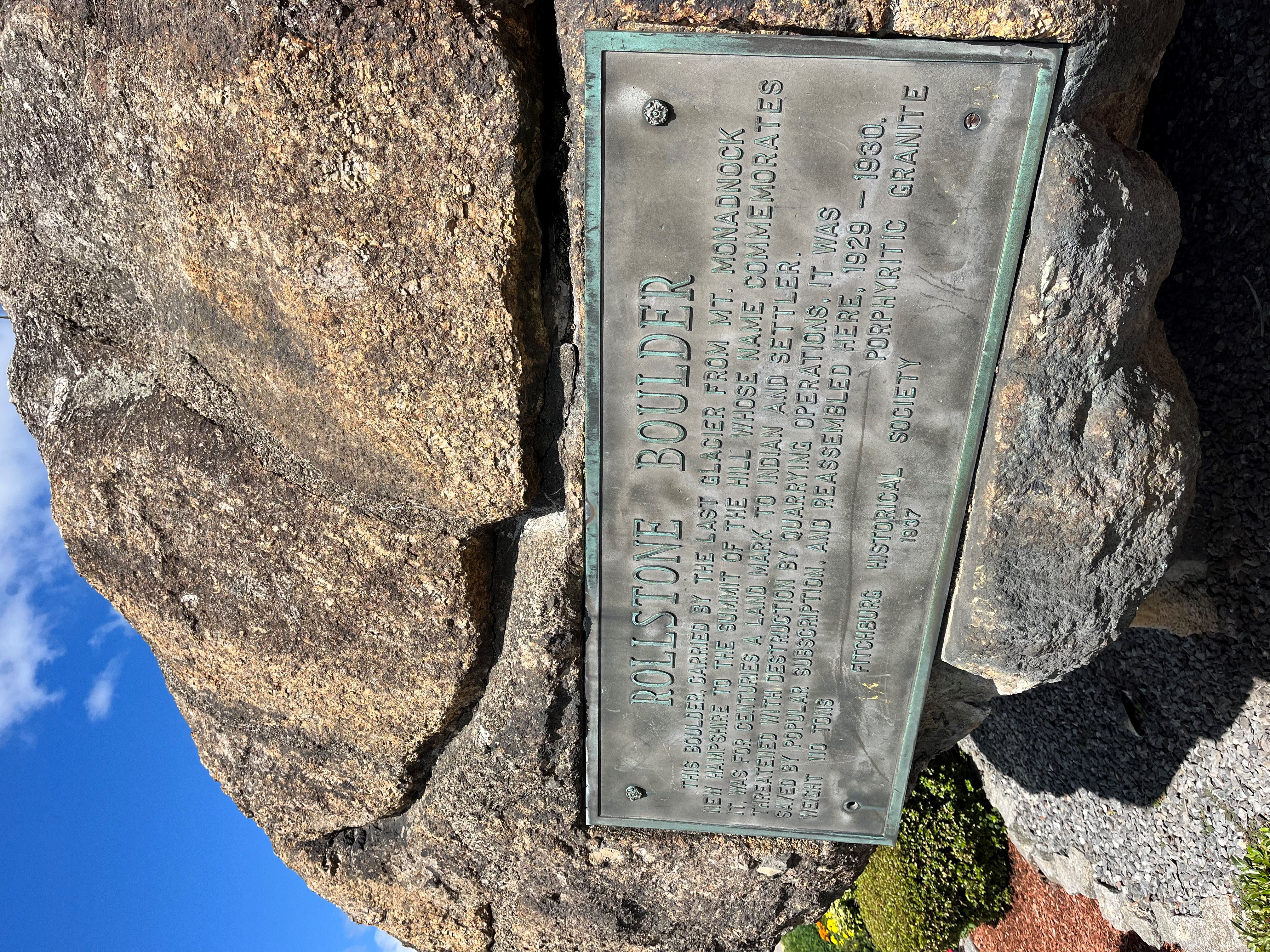

We printed a few scans of her postcards but I decided I wanted to build a show around them, a process that slowly simmered away over the coming years. It became so much more expansive with each artwork I made note of and brought into the fold and the more my research and reading unfurled alongside that. There have been some really interesting full circle moments along the way: last summer, as a part of an unrelated road trip, I coincidentally had the opportunity to visit Rollstone boulder in Fitchburg, Massachusetts: a specific rock that, by way of Meghan’s collection, I had obsessed over for years.

DD: This exhibition follows closely (instantaneously, geologically speaking) after your work as one of the curators for the 2022 edition of the Toronto Biennial titled What Water Knows, The Land Remembers. In the gorgeous exhibition catalogue, Candice Hopkins wrote that “|LS|l|RS|and and water contain histories and hold all that has taken place in their midst, like evidence. Land and water are both bodies and archives. … After all, even soil isn’t fixed. It flows like water over long expanses of time, with the bottom-most layers moving ever so slowly upward, continually surfacing its oldest layers, continually revealing its past.” (p. 70-71). How have the land and erratics in this exhibition worked upon you in terms of flowing, shuffling and revealing? Have you been surprised by any of these moves along the way toward this inaugural expression of the project at KWAG?

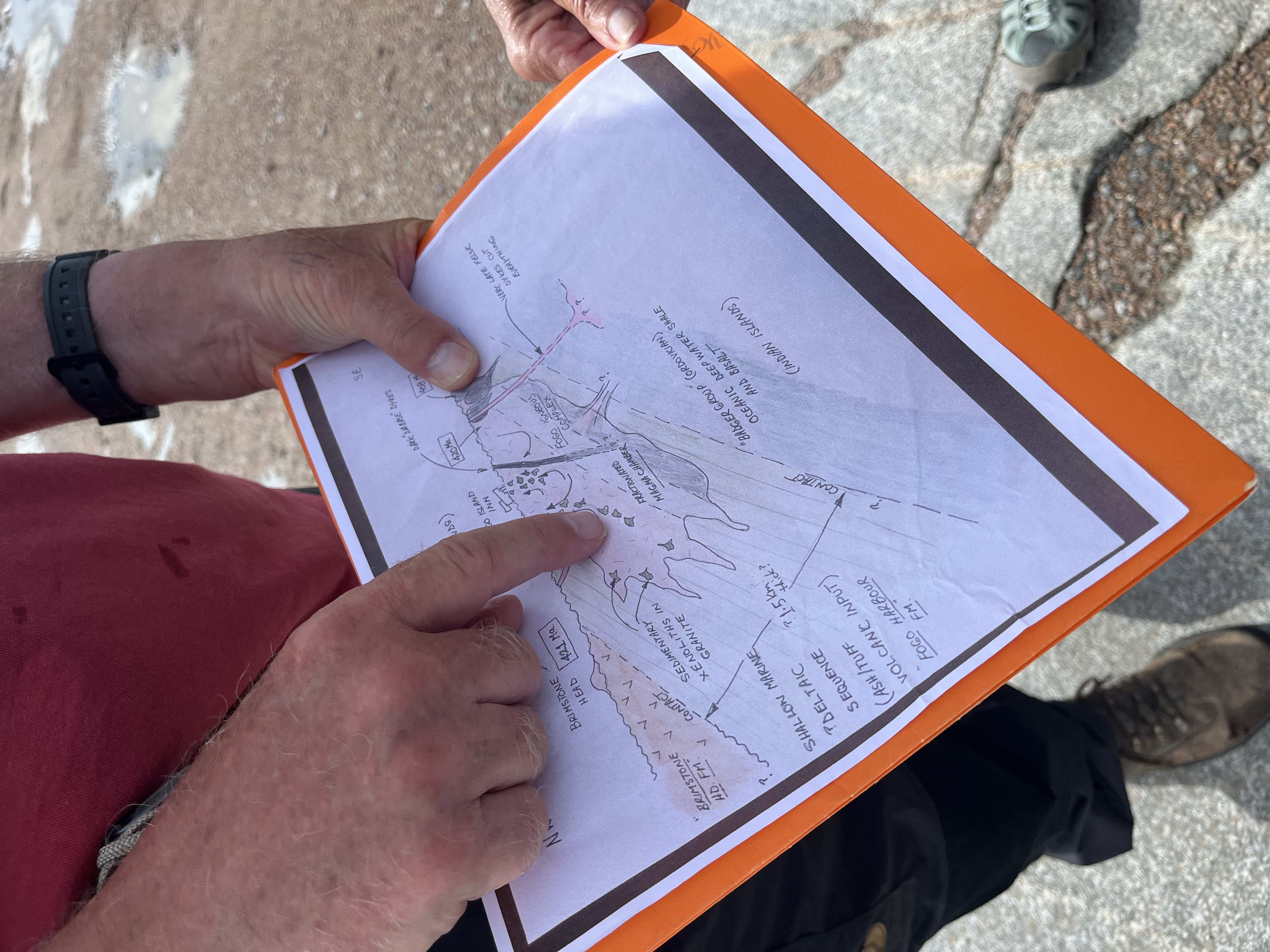

KL: I’m so grateful for the conversations Candice and I had through working on the two Biennials together, and the idea of our environment as a witness to and record of all of human and more-than-human history is certainly present in Erratic Behaviour too. Land and water are active participants in ongoing planetary processes, and the dynamism of earthly matter has been mirrored in the development of the exhibition in that I saw myself as one node in a web of collaborators, materials and influences. I didn’t expect that during my residency on Fogo Island, Newfoundland last year I would cross over with two geologists, affording me the opportunity to have meaningful cross-disciplinary conversations while I was writing about and making sense of this exhibition. By spending time in the field with them, I realized that geologists are fluent in the language of rocks. In their discipline they translate the story of our planet across deep time. They themselves are curious and engaged storytellers, much as I think curators and artists are.

I give a nod to the influence of the conversations I had with Dr. Dough Reusch through the Erratics Behaviour poster, the backdrop of which is an erratic boulder in Tilting on Fogo Island that I spent some time with.

DD: Building on the last question, I have been thinking about this relationship between land and water, memory and knowledge. Of course, in the case of glacial erratics, water is the ice that pushes the earthen body. Taken together, the erratics are a bunch of geologically active bodies dancing and remembering, sometimes making traces and other times seeming to appear out of time itself. I wonder: How is time grounded in the exhibition? Specifically, as you note in your exhibition text, humans continue to exhibit the most erratic behaviour of all - we are running out of time.

KL: Part of what initially drew me to rocks is the way they support contemplation of different scales of time–the extreme brevity of human life compared to the breadth of geologic deep time. Decentering myself and recognizing the relative insignificance of an individual human life reminds me to tread lightly and as much as possible live in a way that supports the lives of generations to come and honours those of our past as a part of the same continuum. There’s a good deal of slipperiness around time in the exhibition, moving between wildly different scales but also moving through disparate moments or cycles of time.

DD: Whenever I think about the environment, and humanity’s extractive, destructive relationship to land, I quickly ask myself about hope when the situation seems to be devoid of any. What is your relationship to hope, and where do you go to find it these days?

KL: Our constant, ever-unfolding and escalating state of planetary emergency weighs on me and often feel overwhelmed by the state of things, I won’t say I’m not. We have losses to grieve. Yet without hope there is no possibility of change, and radical global systems change is what is so desperately needed to help mitigate the disastrous impact of extractive industries, to name but one culprit. It is a bit of a cliché perhaps, but I do find hope in art. Many of the artworks of Erratic Behaviour, as much as they bring much needed criticality to difficult subjects, also have a playful or humorous side, they encourage us to stretch our imaginations, to be ever curious about the world around us.

Otherwise, I’m also very interested in and hopeful about the growing movement to grant legal personhood to bodies of water.

DD: That’s great that you mention the legal personhood for bodies of water. I agree with you, it is an incredibly hopeful and direct action. And there’s no shortage of options. I wrote very briefly about this in the Exhibition Resource Guide for SOS: A Story of Survival, Part II - The Body, where we briefly turned attention toward the Mutuhekau Shipu, a 193 km-long sacred river for the Innu Nation in Québec that was recognized with legal personhood in 2021. It was the first river in Canada to receive this recognition. Bringing us back, what is something that our readers can look forward to from you next? Any exciting projects that you would like to highlight here?

KL: As I write this I’m preparing for a trip to Arles, France, with fellow team mates from the Centre for Sustainable Curating to take part in a residency program at LUMA. They have an atelier that is doing some interesting experiments with biomaterials and sustainable building practices. I imagine this will be generative and further influence the way I go about exhibition-making. Closer to home, I have been working on an exhibition of temporary public art for the City of Barrie that will open in September of this year. Seeds to Sow will take place along Barrie’s shoreline and downtown for six weeks, and you can look forward to an announcement of the participating artists this spring.

KWAG would like to thank Katie for taking the time to share these ideas and resources. If you enjoyed this conversation, and would like to engage in related discussions in a more sustained form, we invite you to attend our upcoming hybrid event, Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements, with Jane Mah Hutton and Katie Lawson on Thursday 4 April from 7:00 - 8:00 p.m. at KWAG. The event is free to attend, but RSVP is required.

Katie Lawson is a curator and writer based in Toronto. She was a curator for the Toronto Biennial of Art, working with Candice Hopkins and Tairone Bastien on the inaugural 2019 and 2022 editions. She has also curated exhibitions at Images Festival, Toronto (2023); MacLaren Art Centre, Barrie (2021); the Art Museum at the University of Toronto (2018); the Art Gallery of Ontario (2018); Y+ Contemporary, Scarborough (2017), and RYMD, Reykjavik (2017). Katie is a graduate of the Master of Visual Studies Curatorial program at the University of Toronto, where she previously completed her Master of Arts in Art History. She is currently working towards a PhD in Art and Visual Culture at Western University, with an interest in contemporary art and climate change. Lawson was awarded the Hnatyshyn Foundation Fogo Island Arts Young Curator Residency in 2023. She contributes writing to a range of print and online publications.

All images submitted by Katie Lawson, © 2023.