The following transcription was taken from a conversation between Dr. Nehal El-Hadi and Jessica Karuhanga on 4 March 2023. Nehal and Jessica have collaborated on writing and programming for over six years, beginning with Ineffable Blaze, an exhibition curated by Jessica at Trinity Square Video (Toronto) in 2018. They reunited again to talk about subjectivity, representation and relationality in Jessica’s practice. The text has been edited for concision and clarity.

Dr. Nehal El-Hadi (NE)

Your work in this exhibition reflects different modes of intimacy: the interiorities and subjectivities of yourself and other women featured. Body and Soul, for example, is an intimate topography of your own body.

Jessica Karuhanga (JK)

The iteration of Body and Soul in the exhibition is actually a remake. I originally conceived this piece when I was in graduate school in 2012, and then I lost that video file. But it was a very important piece to me. It's a video of my torso in front of a white backdrop, and my torso is covered in tumours caused by my genetic conditions.

I’m interested in this obsession with landscapes and regionalism within Canadian cultural history, and I was thinking of my body as a landscape. But I'm also thinking about it in terms of place and origins, where I come from. I’m first-generation on my dad’s side — he's a refugee from Uganda — and my mom is of mixed British and Romany heritage. Those origins have a kind of rootlessness, so I started with my body.

I made this work understanding that folks are going to invariably see this and imbue it with meaning around the medicalized body. I was really interested in how skin is read in terms of disability and race. I was also thinking about the white cube of an art institution, but also the blank walls that you might encounter in a hospital space. What new meanings are generated when my skin is projected onto a wall? It wouldn’t have the same effect if the video was played on a monitor at all.

The audio track is meditative breathing, placed slightly disjunctive — not everyone notices that. You might see my stomach rising while you're hearing an exhale.

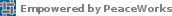

There’s another work in the exhibition, on the other side of the wall from Body and Soul called no other findings. That work uses calibration scans from an MRI machine that appear to be abstract images, but they contain more information than the video behind it. But if you don't understand that language or understand how those machines work, the full context will not be legible. What is legible? What can be translated? I’m interested in how to reflect, deflect and refuse legibility.

NE

It’s a bit weird to talk about the Black body in art when I’m talking about your actual body, and I can see you through the computer screen right now. But I’m thinking of Coco Fusco’s The Bodies That Were Not Ours, where she describes the response to Black artists’ work that uses their own bodies: “The extraordinarily high level of anxiety regarding the presentation of the black body in the arts and media is one of the most visible, lasting effects of an historical black experience in the diaspora.”

JK

It's definitely something that I struggle with. Part of me wanted to move away from performance because I was tired — the work is demanding. But there’s also an entitlement that non-Black folks have to the work. Not just to the work or the object, but my body and my subjectivity, so it feels like this desire or entitlement to my spirit. I do think that it happens with performing artists — there's a point where you see people expire or retire or they disappear, and it doesn't seem to be the same with non-Black performers.

If I'm looking at the history of art with performance artists, there’s often the nude and naked bodies. Whose bodies are those, and what conditions in prehistory, maybe, informed that? So there's an aesthetic. Part of me wanted to move away from performance because I was burned out and I felt like returning to painting and sculpture.

I ended up moving more into film, where you're still dealing with the image and representation, but it feels safer than performance art. I don't think that it's a coincidence that a lot of performance art is by disabled, Black and Indigenous artists, queer artists, whether we're talking about drag or spoken word, whatever it might be. There's a bit of expectation of how you're supposed to act or perform. I'm always trying to find ways to circumnavigate or penetrate or disrupt those kinds of expectations.

NE

In Embodied Avatars: Genealogies of Black Feminist Art and Performance, Uri McMillan describes Black women performance artists as “wielding their bodies as pliable matter” to assume objecthood as a strategy. McMillan writes that “performing objecthood becomes an adroit method of circumventing prescribed limitations on black women in the public sphere while staging art and alterity in unforeseen spaces.”

JK

Maybe that's a better way to articulate what I'm trying to do. It is performing objecthood in the anticipation of already knowing how non-Black people read us. I'm already being watched. Even when I'm not performing, I feel that being-read happening.

NE

McMillan describes that the works of Black women performance artists in turn “make the spectators subject to their presence.” It’s an apt way of describing how your work — at least in both my experiences of it and witnessing others experience it — has a way of implicating the viewer.

JK

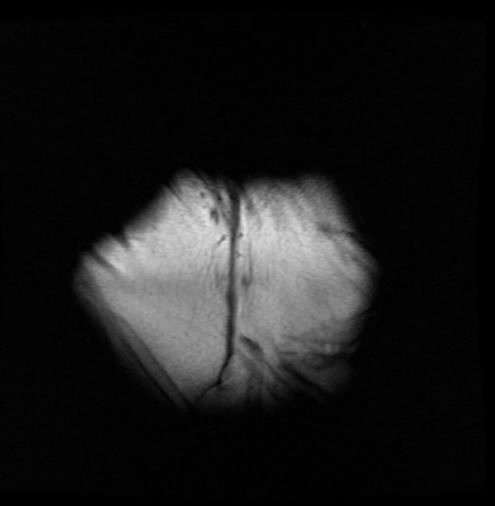

That's exactly what I was trying to do with the sculpture through a brass channel. I’m always thinking in these experiential terms, and insisting that the audience is not a passive receiver. Even if we're talking about viewers, I want the audience to understand and know that they are complicit in this exchange. I've always really appreciated art that does this — maybe I didn’t realize it in the moment of viewing it, but later I’m like, “oh, I'm the subject of this.”

through a brass channel consists of a copper pipe delicately balanced on a brass bangle, which in turn rests on a masonry stone from the wall of a building. The bangle is from my father’s jewelry collection that he used to bring to trade shows of African artefacts and objects. I really love those bangles: they're just beautiful, but they remind me of shackles. They were also a form of currency. The copper pipe is a conduit or channel, and functions as a placeholder or metaphor. Structurally, the whole thing is a little bit precarious.

NE

As your approach developed over time, you started including other Black women in your work. Some of them are friends, others are artists. I’m curious about this expansion and inclusion in your practice, this literal growth of your concepts and executions, especially considering that your earlier work centred yourself.

JK

I felt it was important to start with myself as material. What often happens to Black artists is their practices can become faced with a reductive understanding of what representation means. And there's such a short history of us actually being able to self-articulate — to paint, draw and document our own lives. So understanding that, it felt important to start with myself and my own origin stories as a point in a constellation of Blackness, because it isn't a monolith.

I've never been interested in being a representation of a community. In fact, I think that's just a tool that non-Black audiences use to categorize the type of art that artists such as myself make.

Before I bring other folks in, there’s an ethical question around care, because how can I? How can I start making art and bringing other Black women into the fold? If I can't protect myself, how could I possibly position myself as a host and protect them as well? I had to be absolutely sure that I understood what the parameters of my artwork are, especially because my works are always deeply autobiographical: it's a private or sanctified space. So it felt necessary that I figured out my own complicity in using myself as material before I even asked other folks to join me in my work.

About Nehal El-Hadi

Dr. Nehal El-Hadi is a writer, editor and researcher investigating the relationships between the body (racialized, gendered), place (urban, virtual) and technology (internet, health). She completed a Ph.D. in Planning at the University of Toronto, where her research examined the relationships between user-generated content and everyday public urban life.

Nehal is the Science + Technology Editor at The Conversation Canada, an academic news site, and Editor-in-Chief of Studio Magazine, a biannual print publication dedicated to contemporary Canadian craft and design. Nehal sits on the Board of Directors of FiXT POINT Arts & Media and the Provocation Ideas Festival.

Her current research projects explore human- sand relations, the cultural impact of white sandalwood regulations, and the long-term implications of surveillance. Nehal advocates for the responsible, accountable and ethical treatment of user-generated content in the fields of journalism, planning and healthcare. Her writing has appeared in academic journals, general scholarship publications, literary magazines and several anthologies and edited collections.

Jessica Karuhanga: Blue as the insides will be on view at KWAG until 6 August 2023.

Images: |LS|1|RS| Dr. Nehal El-Hadi. Photo by Gillian Mapp. |LS|2|RS| Jessica Karuhanga, no other findings, 2021. Single-channel video. 01:15 mins. |LS|3|RS| Jessica Karuhanga, through a brass channel, 2017. Copper pipe, brass bangle, stone. Photo by Scott Lee. All images courtesy © of Jessica Karuhanga.